The Continual Struggle

The American Freedom Movement and the Seeds of Change.

The Continual Struggle is artist Brian Washington’s ongoing body of artwork documenting the Civil Rights Movement and America’s historical struggle against segregation and other forms of race-based disenfranchisement. The Continual Struggle employs visual art as a means of storytelling, vividly recalling a time when people were willing to go into the streets to protest injustice and inequality.

Part One

The Sharecropping Years

Freedom’s Strange Birth

“[T]he slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery...”

Throughout much of the twentieth century, a time when most African Americans either lived in the Deep South or where one generation removed from their southern roots, segregation was the law of the land. The first sharecroppers were the former African American slaves. Under the sharecropping system, African American families would rent small plots of land in return for a portion of their crop, to be given to the landowner at the end of each year.

Despite the abolition of slavery, the landowners under the sharecropping system continued to largely control the lives of the African Americans working their land. What began as a device to replace slavery became a pernicious system that entrapped African American farmers, ensuring that they remained poor and virtually locked out of any opportunity for land ownership or basic human rights. It is here that struggle for equal rights, a Continual Struggle, began.

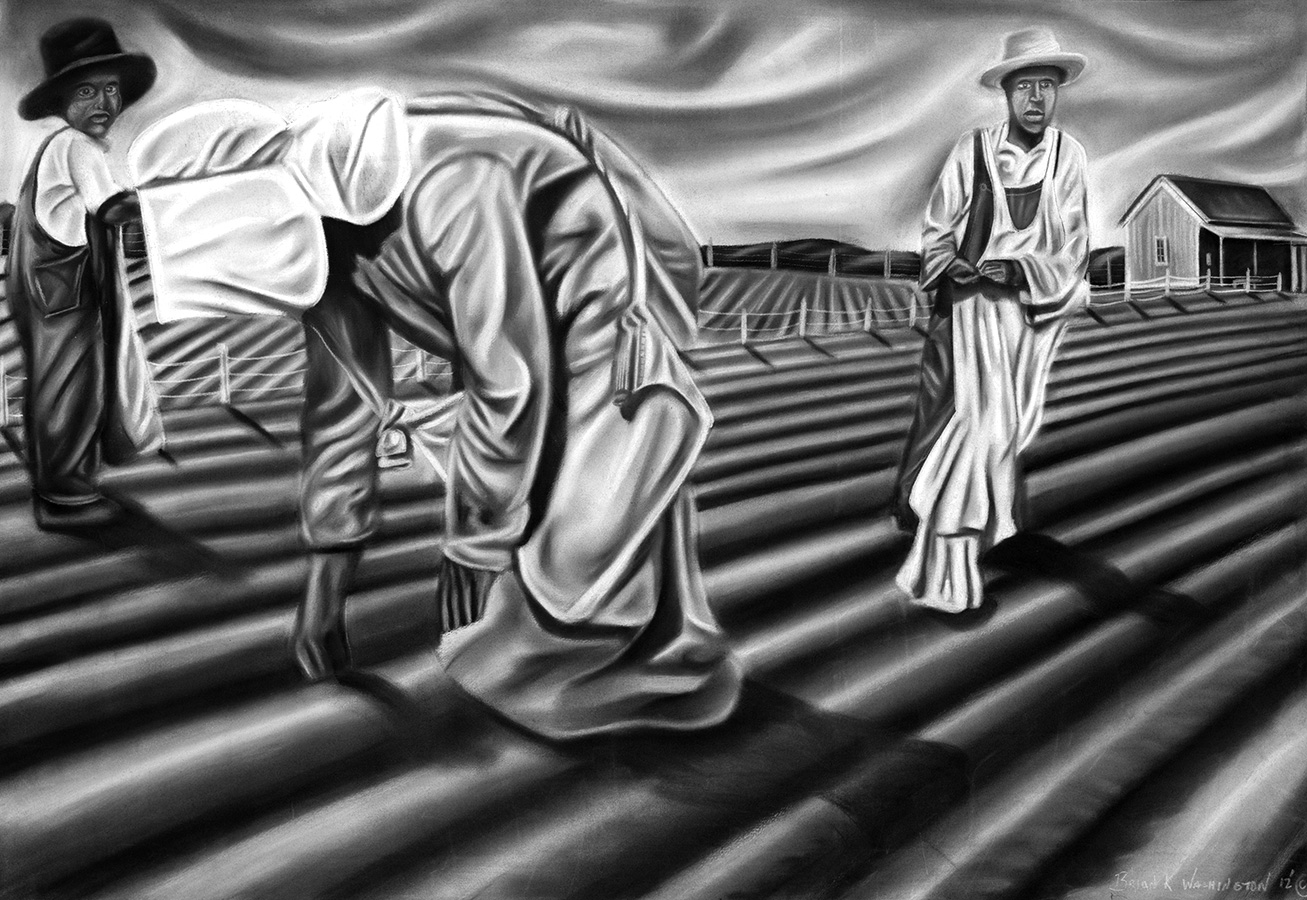

The Cultivators

In the early years of Reconstruction, most African Americans in rural areas of the South were left without land and forced to work as laborers on large white-owned farms and plantations in order to earn a living. Many clashed with former slave masters bent on reestablishing a gang-labor system similar to the one that prevailed under slavery.

In an effort to regulate the labor force and reassert white supremacy in the postwar South, former Confederate state legislatures soon passed “black codes” -- restrictive legislation denying blacks legal equality and political rights, and requiring them to sign yearly labor contracts aimed at forcing them back onto the plantations. Authorities often put freed African Americans in gangs to work plantations, despite the abolishment of slavery.

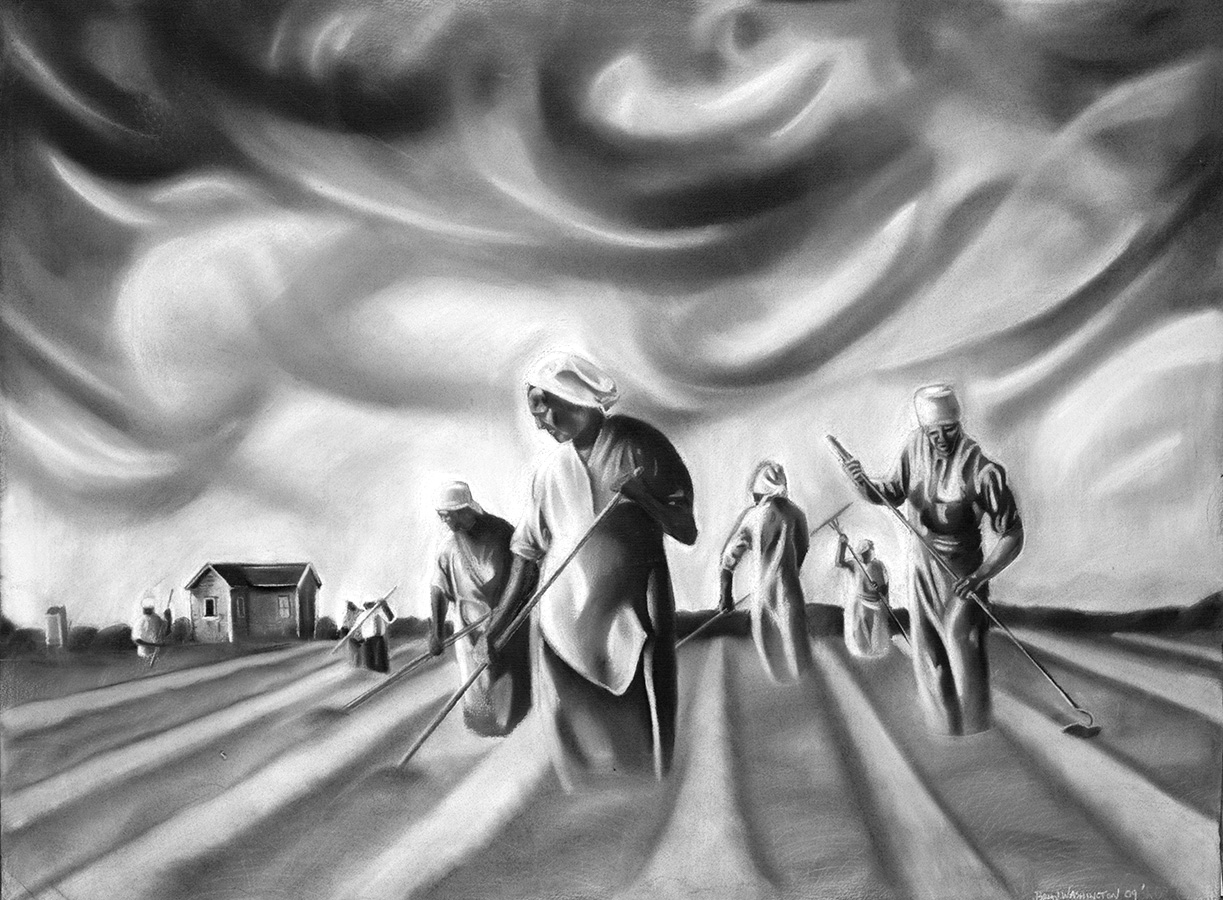

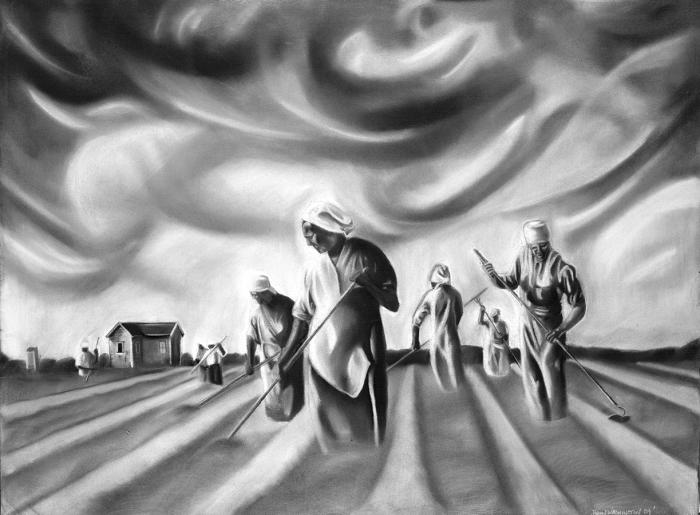

The Cultivators

In “The Cultivators” Washington depicts a traditional gang labor arrangement, in which field workers were typically divided into three gangs, the first gang reserved for the strongest and fittest workers, and the third reserved for the weakest. These groups included African American children, teenagers, old people, and even those who were sick.

They Were Very Poor But Loved

While sharecropping gave African Americans autonomy in their daily work and social lives, it often resulted in sharecroppers owing more to the landowner than they were able to repay. Many African Americans went into debt or were forced by poverty or the threat of violence to sign unfair and exploitative contracts that left them little hope of improving their situation.

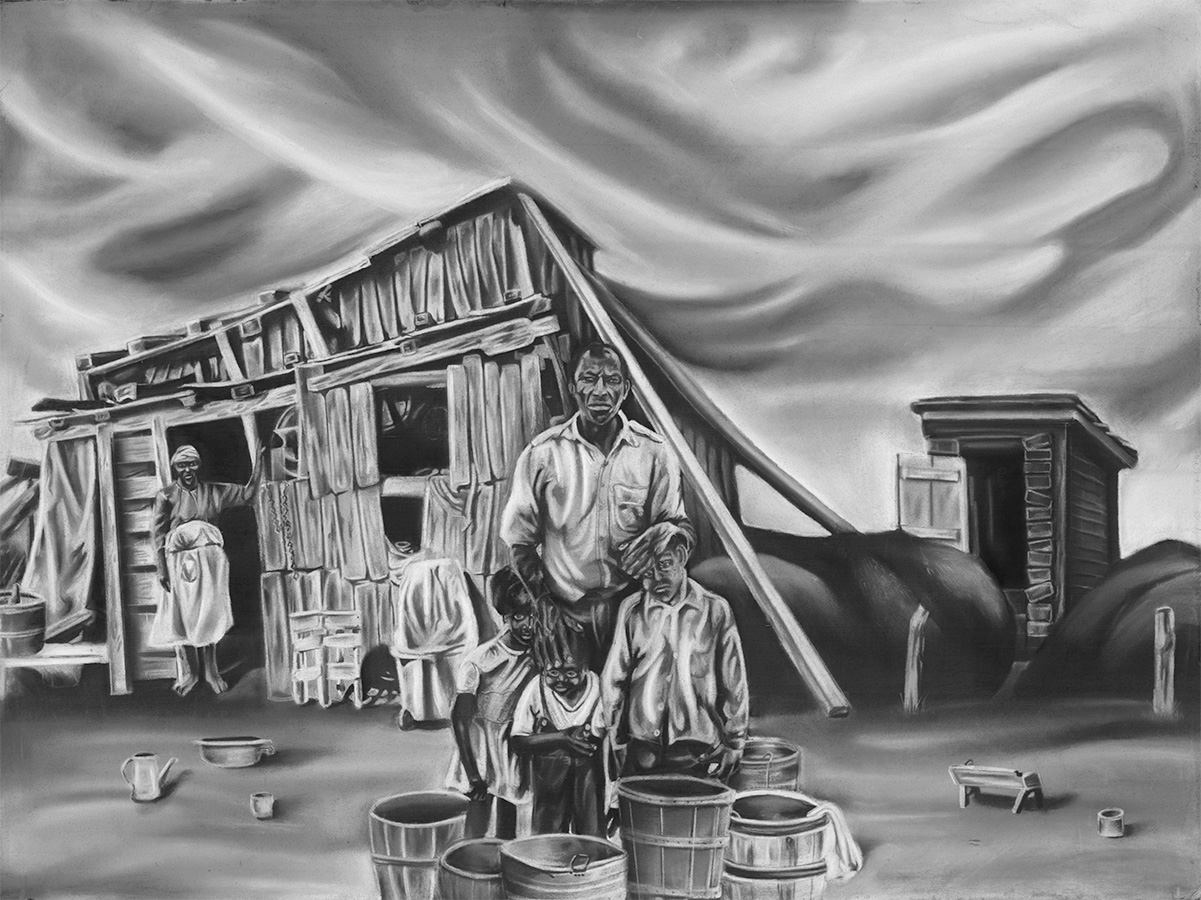

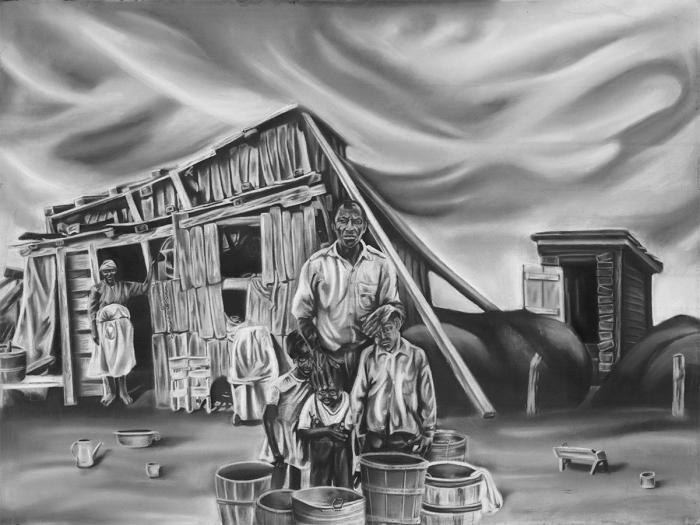

They Were Very Poor, But Loved

In “They Were Very Poor, But Loved,” Washington intricately depicts the plight of the sharecropper family. Sweeping clouds are invoked by Washington to indicate turbulent times. The hard, backbreaking work of the sharecropper led to stooped, physically destroyed, and mentally blighted black people who could seldom envision escape for themselves or their children. Their lives were an endless round of poor diet, fickle weather, and the unbeatable figures at the company store. However, the family bond was rarely broken by such dire circumstances.

“They Were Very Poor, But Loved,” depicts a father figure with exaggerated hands that are symbolically big enough to provide for and protect his family. The young men stand out in the front, learning from their father. The daughter, her father’s jewel, stands off to the side and in a guarded posture -- a position emphasizing a father’s love for her that is undeniable.

The mother gazes upon the family protectively from the house, dressed in her apron. The house, held together with sweat, love and a few boards -- is home to this family and no doubt dreams of a better life for their kids are buried in a bible inside.

The outhouse, and the buckets and barrels, rendered in high detail, are an attempt by the artist to bring the viewer into this time in American history, complete with the emotions and pain that were inescapable.

Kin Folk

Sharecropping was a family undertaking. No one could be spared from the fields to watch over a small child during the planting and harvesting seasons. As soon as they were able to walk, the children of sharecroppers participated in the daily rigors associated with farming, laboring alongside the rest of the family. Sharecropping did not provide African American families with any sense of hope or deliverance.

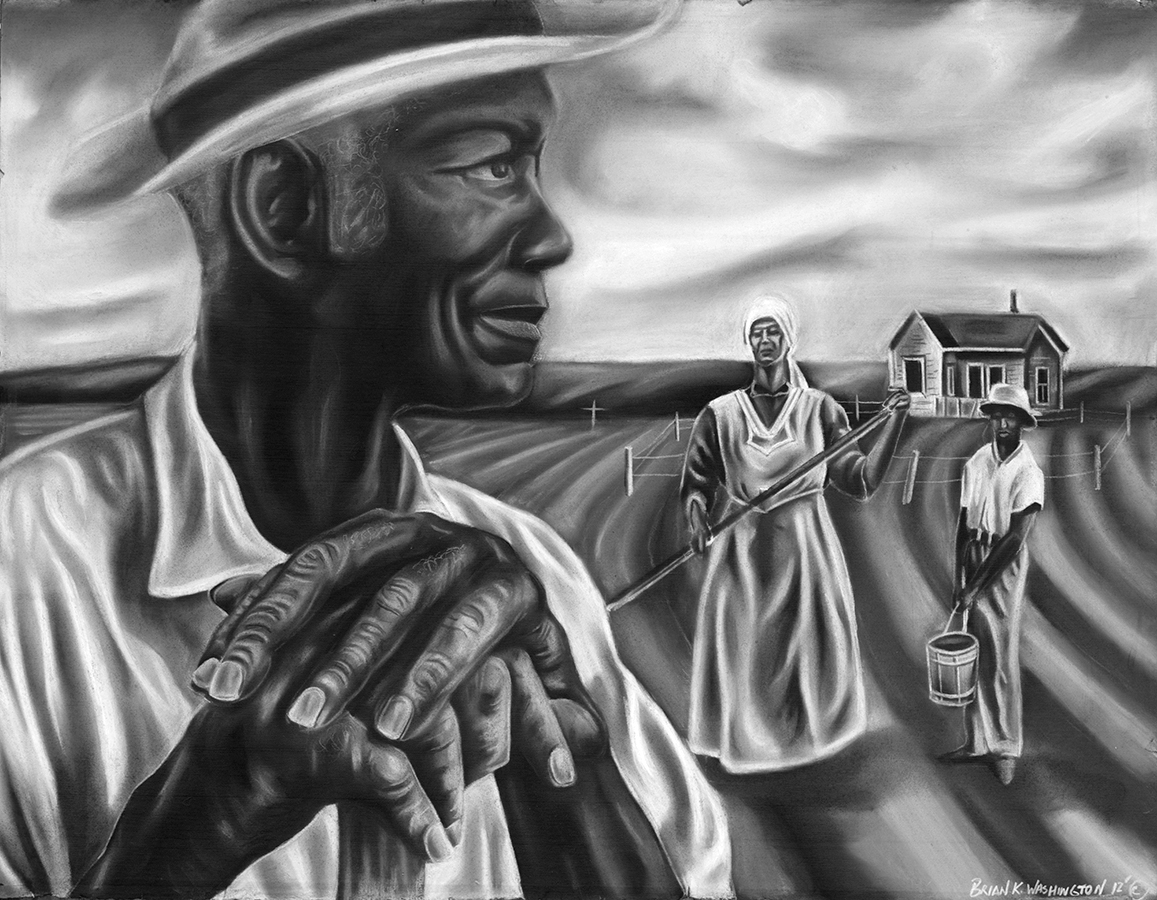

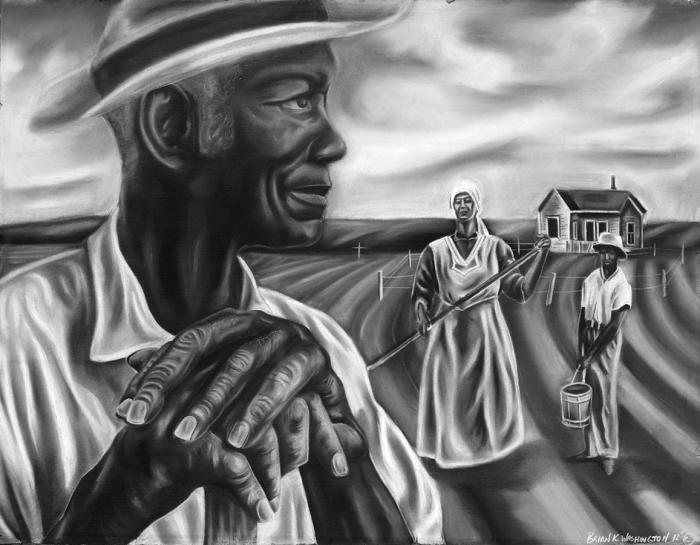

Kin Folk

In “Kin Folk,” Washington depicts a sharecropper family completing a typical day’s work on the land. The father, protector of the family, is prominently featured in the foreground. He holds a stoic gaze that not only indicates his worries for the well-being of his family, but also a steely resolve for a better life. The mother stands in the back by their child, who has stayed home from school to help work the land.

Given the circumstances of the time and the poor resources available to sharecroppers, infant mortality amongst sharecropper newborns was extremely high. Washington acknowledges this horrid fact in “Kin Folk,” depicting a cross-shaped grave in the distant background of the field -- which houses a deceased member of the family that was tragically lost at birth.

To the Disinherited Belongs the Future

Under slavery African Americans were never compensated; under sharecropping they worked and were rarely paid and ended up in debt. This system, which occurred in literally thousands of African American households across the South, robbed many children of their early life, a devastating effect that could last a lifetime. Nevertheless, the family bond was an important aspect of coping and survival for the sharecropper child.

To the Disinherited Belongs the Future

In “To The Disinherited Belongs The Future,” Washington depicts a sharecropper father and his son, embarking on a day’s work on the land. The son, his father’s pupil, is positioned in a mirror image of his father – indicating the son’s eventual role as the burden bearer for the family’s next generation. However, the father’s intense gaze suggests a different desire -- for the son to eventually enjoy a life not burdened by systematic and institutionalized disenfranchisement. This goal was eventually accomplished through the subsequent gains of African Americans during the Civil Rights Movement. In this sense, to these “disinherited” sharecroppers (and others like them), the future was theirs.

Sharing The Burden

Sharecropper women helped the family economy by stretching the scarce resources as far as possible. The role of the women involved them cooking, cleaning, and tending their gardens. They sewed the family clothing and knitted socks and winter hats. Old coats and dresses were turned inside out to make them last longer. They even conducted arduous and back-breaking work in the field.

Sharing The Burden

In “Sharing The Burden,” Washington illustrates the far-reaching family contributions of the sharecropper woman. With every hand needed in the fields to make ends meet, the entire sharecropper family, including women and children, were required to “share the burden” for survival in the Reconstruction era American south. Washington postures the women featured in “Sharing The Burden” with grace and dignity, yet imbues their facial expressions with a sense of underlying sadness -- an outward indicator of the overwhelming stresses placed on every member of the sharecropper family.

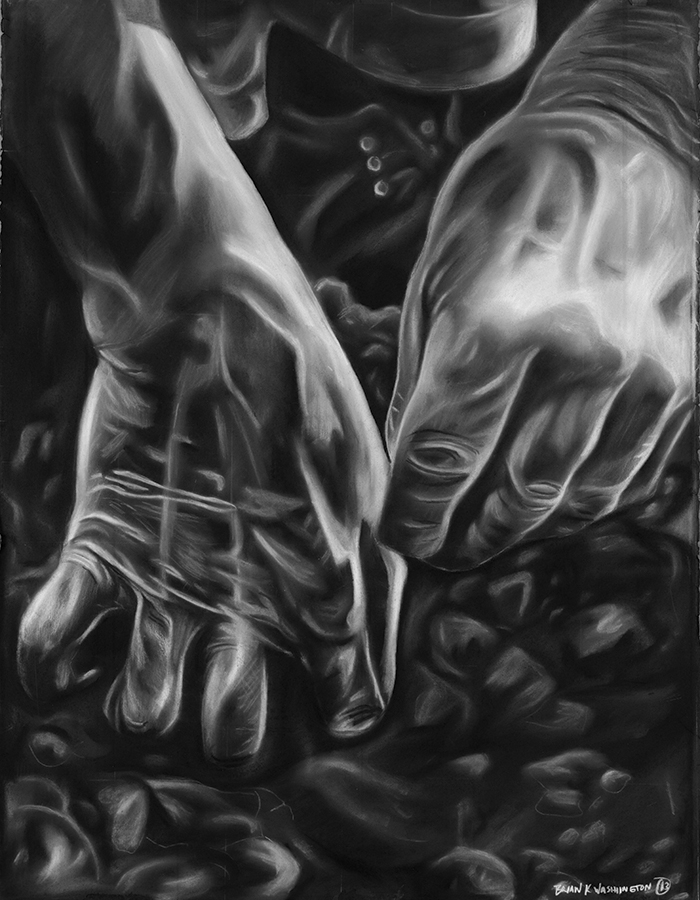

With These Hands

Sharecropping involved back-breaking labor such as plowing, planting, weeding, and harvesting -- and this included the children. The work of cultivating crops was not easy. Physically the work led to back problems, bad knees, and arthritic hands. For the sharecropper, overcoming the physical maladies of daily field work was a matter of survival.

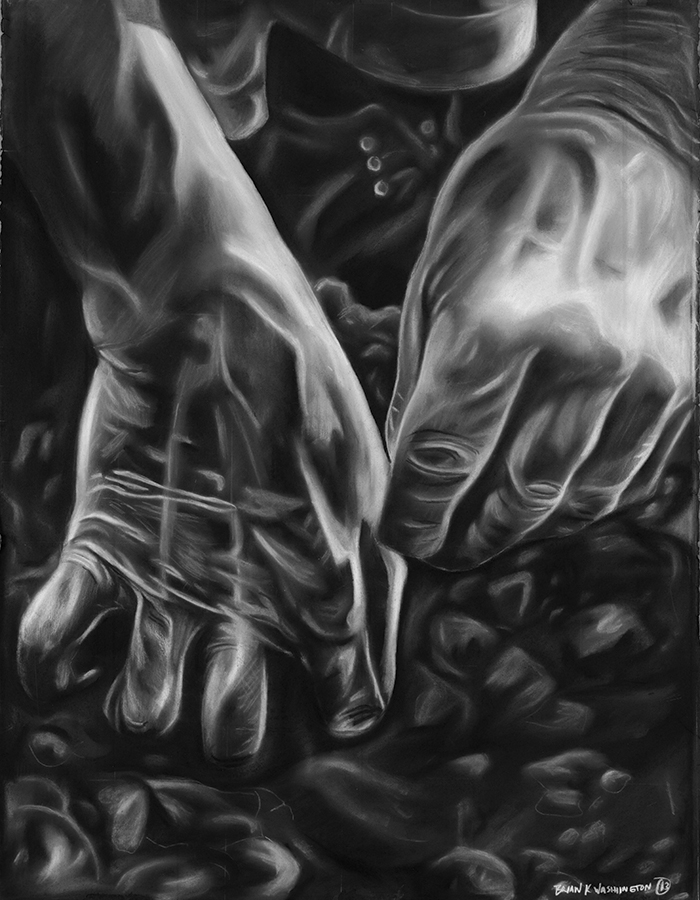

With These Hands

In “With These Hands” Washington depicts the weathered hands of a sharecropper tending to the land. The hands -- swollen and battered by years of hard work and toil – are intricately rendered to illustrate the physical agony and bodily anguish that was common to sharecropper life.

A Joyful Sorrow

Sharecropper children were expected to contribute to the household work. Instead of attending school, they would stay home when there was work to be done, especially when it was harvest time. In reality, African American children of sharecropping families of the South faced a life where their labor was valued more than their education and their bodies more than their minds.

A Joyful Sorrow

In “A Joyful Sorrow,” Washington illustrates the inherent contradiction raised by the institution of sharecropping. While sharecropping was touted as a prospect of new economic opportunity for freed slaves, it truly functioned to ensure African Americans remained poor and virtually locked out of any opportunity for land ownership or basic human rights. In this sense, sharecroppers and their families experienced the “joyful sorrow” of superficial freedom, tinged with the shackles of a still existent economic and social slavery.

The central figure in “A Joyful Sorrow,” is a mother figure, whose back is distorted by the constant physical pain of working the fields day after day. Her efforts, as well as those of her children, are in a futile attempt to repay the family’s never-ending debt owed to the property owners. Her face is completely obscured in this back-breaking posture, a subtle detail invoked by Washington to emphasize the lack of humanity afforded to freed slaves in Reconstruction years of the American South.

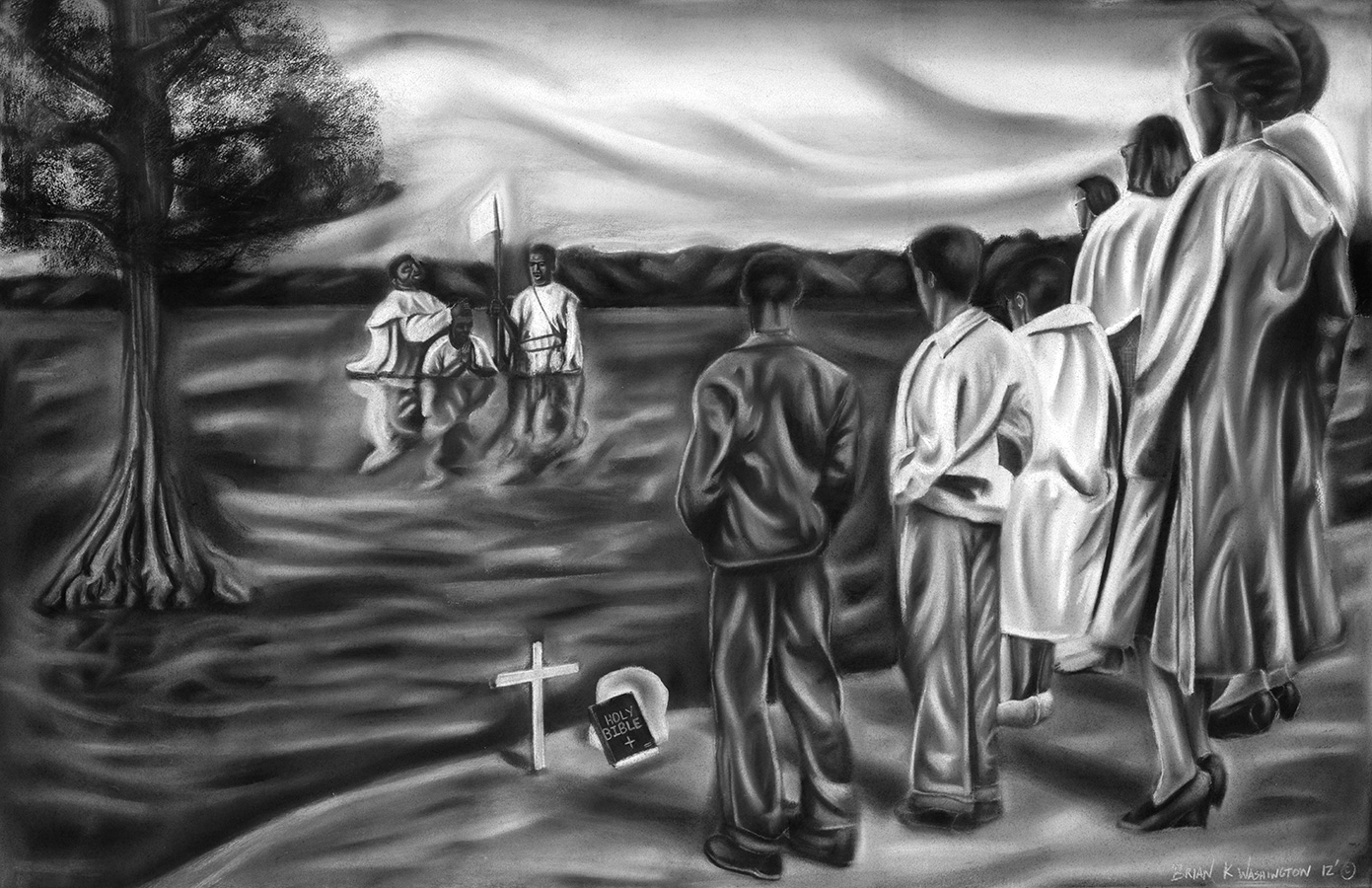

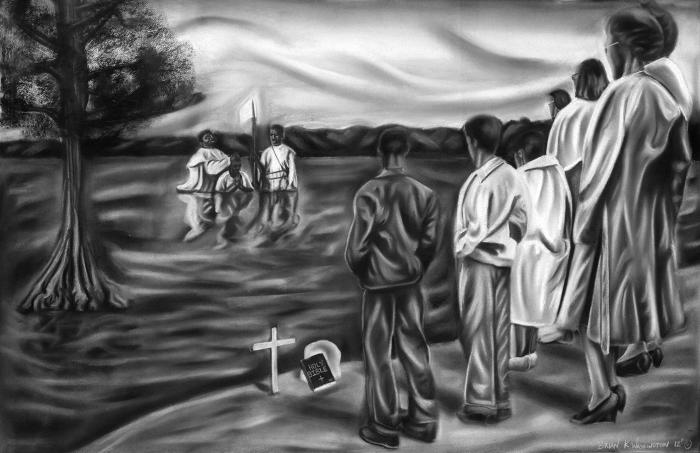

A Paradigm Of Unbroken Rituals

For the great mass of African American sharecroppers, the only thing to lean on was God and the church. Gone were the rights and protections and the promise of emancipation. In their place, the system of sharecropping became the dominant economic arrangement of the entire South.

A Paradigm Of Unbroken Rituals

In “A Paradigm Of Unbroken Rituals,” Washington depicts a traditional river baptism, a rite of passage for African American Christians in the South. This sacred ritual, a symbolic act of purification and initiation, was performed in rivers, bayous, and lakes throughout southern America.

Washington depicts members of the church congregation gathered in excitement on the bank to witness the baptizing of a loved one. In the backdrop, the candidate is immersed in the water. Deacons lead a devotional consisting of the singing of hymns, scripture reading, and prayer.

Part Two

The Civil Rights Struggle

The Price of Progress

“The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions have been born of earnest struggle. If there is no struggle, there is no progress...”

Nearly 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation and after the decline of sharecropping in the southern states, African Americans still inhabited a starkly unequal world of disenfranchisement, segregation and various forms of oppression, including race-inspired violence. “Jim Crow” laws at the local and state levels barred them from classrooms and bathrooms, from theaters and train cars, from juries and legislatures.

In the turbulent decade and a half that followed, civil rights activists used nonviolent protest and civil disobedience to bring about significant social change. Courageous individuals, both black and white, challenged the status quo. They risked—and sometimes lost—their lives in the name of freedom and equality.

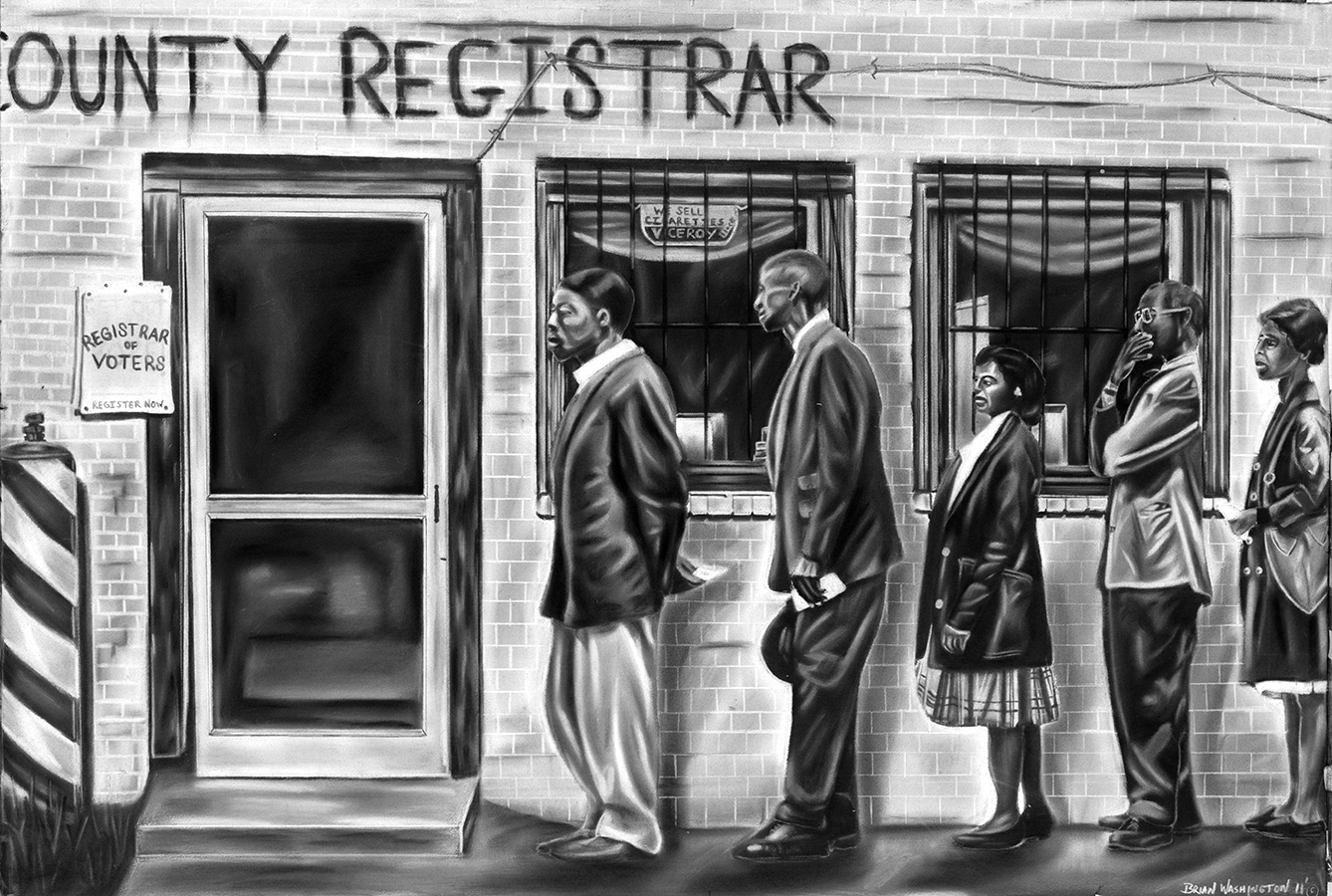

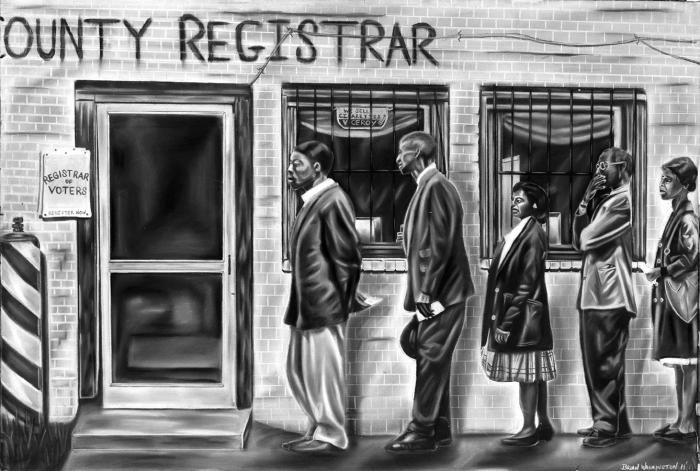

A Study Of Impatient Patience

By the mid-20th century, preventing African Americans from voting had become an essential part of the country’s culture of discrimination. Registrars used the literacy test to keep African Americans off the voting roles by creating standards that even highly educated people could not meet. In addition, employers fired blacks who tried to register, and landlords evicted them from their rental homes. Despite these actions, over the following years, African American voter registration campaigns spread across the American south.

As African Americans began their first voter registration projects in the south, their efforts were met with violent repression from state and local lawmen and other segregationists. These voter registration campaigns eventually became as integral to the Freedom Movement as the desegregation efforts -- and ultimately resulted in passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which had provisions to enforce the constitutional right to vote for all citizens.

A Study Of Impatient Patience

In “A Study of Impatient Patience,” Washington depicts a group of African Americans assembled for voter registration at a local county registrar that could have been anywhere in the South during the segregation years. They have arrived early, prior to the registrar’s opening. Blatant and unobstructed attempts at violence often accompanied such registration campaigns. These prospective voters proudly stand resolutely one after the other, stoically bracing themselves for whatever obstacle may arise as they attempt to exercise their constitutional right to vote.

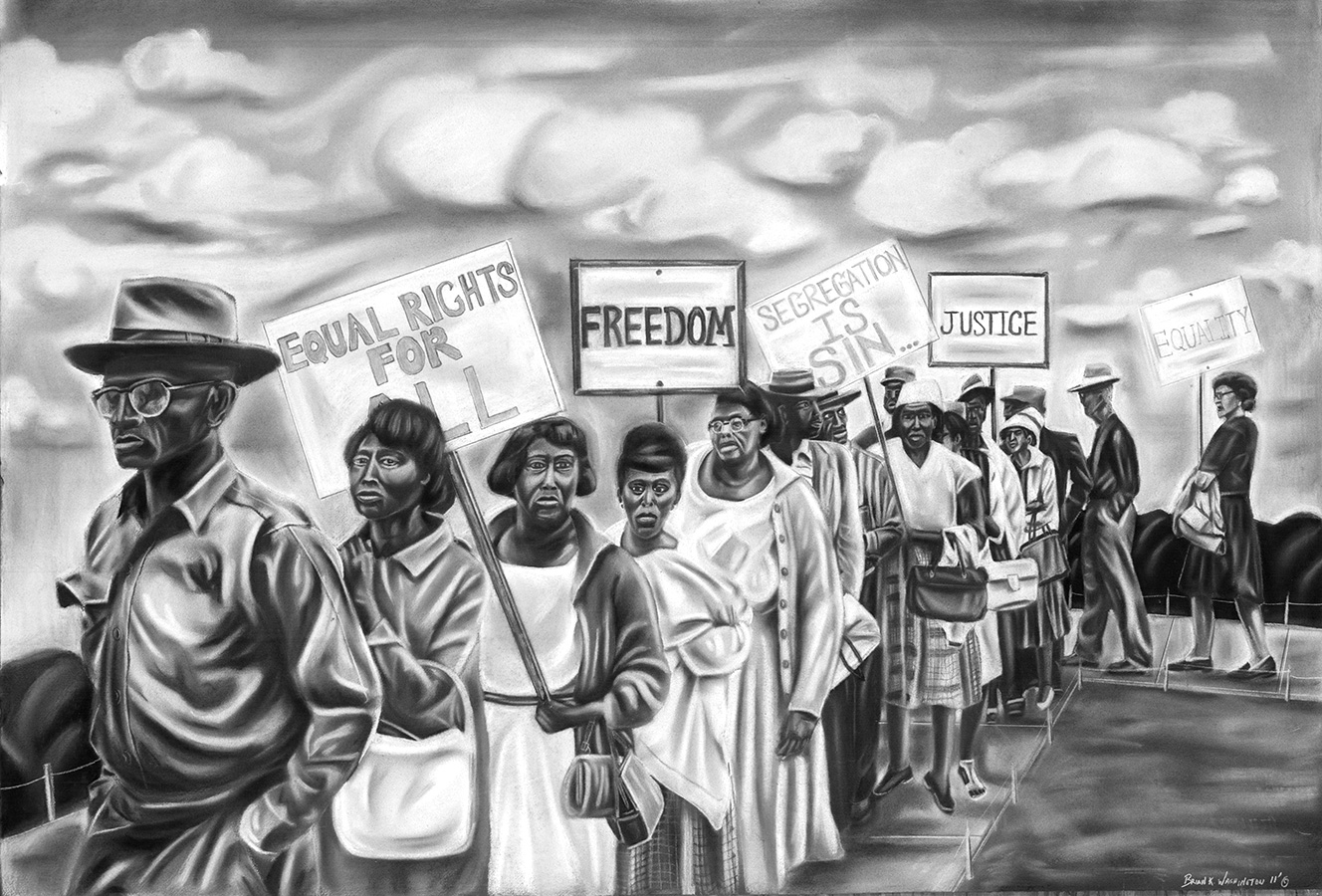

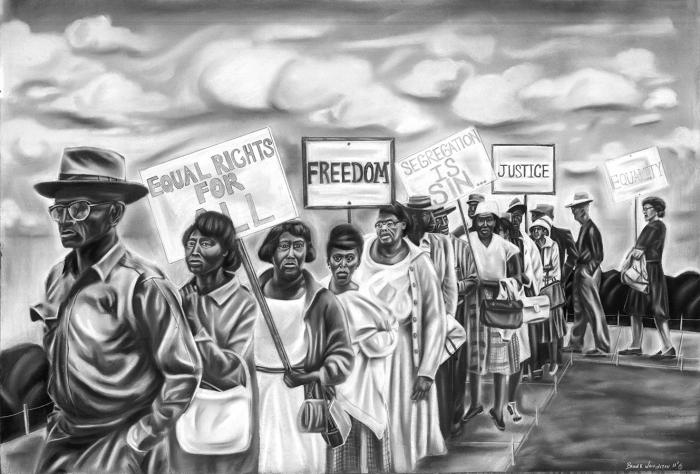

A Parade of Sympathies

Civil rights activists fought inequality in their communities by standing up for themselves and using peaceful and nonviolent tactics. The use of nonviolent protests led to important progress in the integration of the South.

A Parade of Sympathies

In “A Parade of Sympathies,” Washington depicts a traditional Civil Rights era protest scene, which could have taken place in many southern cities during the mid 20th century. All of the protesters in this scene are fighting for the same overarching goal -- equal rights irrespective of race, color, or creed.

However, as evidenced by Washington’s painstakingly detailed rendering of each protester’s face, the deprivation of equal rights has affected each protester’s life in its own independent way. As the line of protesters stretches backwards to what seems like a distant vanishing point, each of the protester’s facial expressions evidence a different emotion. In this respect, the totality of the protest line represents a “parade of sympathies” for the viewer to experience and take in as their own.

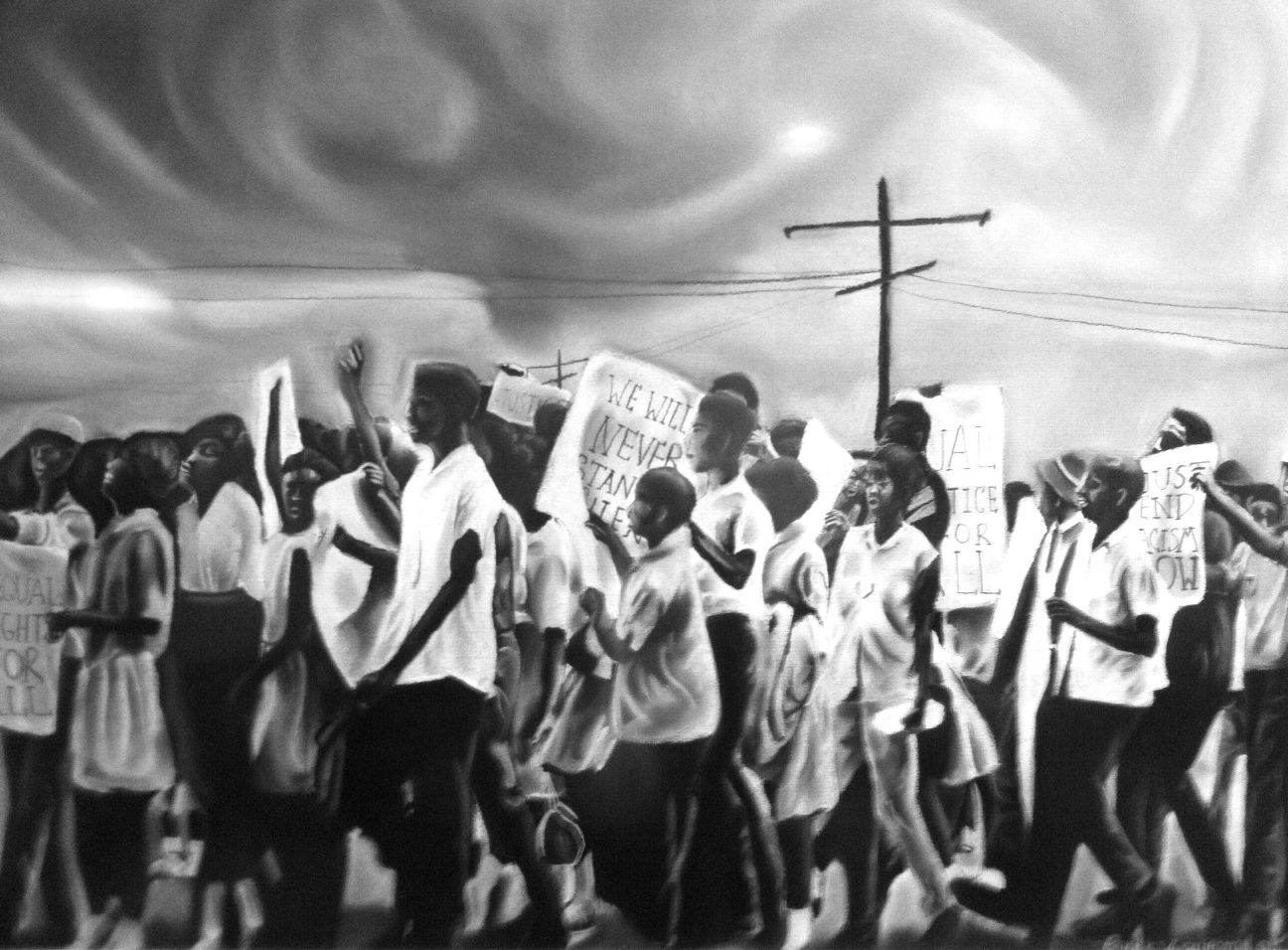

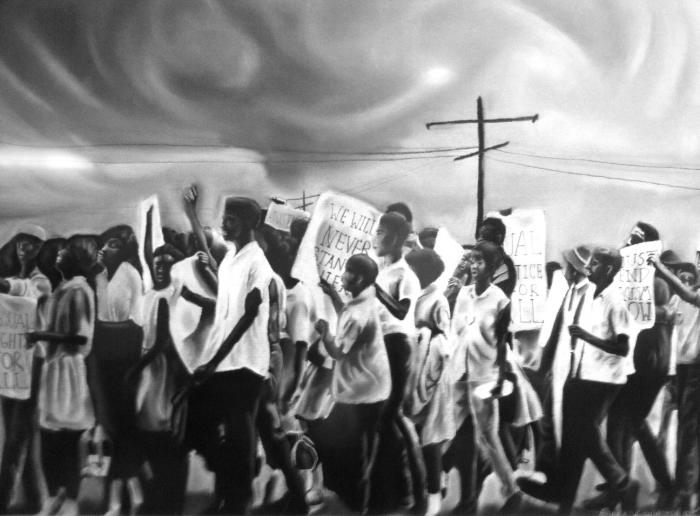

We Will Never Stand Silent

Throughout the nation, hundreds of nonviolent civil rights protests challenged long-established patterns of segregation and discrimination. These included demonstrations, voter registration drives, lunch counter sit-ins, church kneel-ins, and other tactics aimed at integrating public facilities.

We Will Never Stand Silent

In “We Will Never Stand Silent,” Washington depicts a civil rights demonstration that includes protesters from the entire spectrum of African American life -- including men, women, children, and teenagers – who are protesting the Jim Crow laws that relegated them to being second class citizens. Their protestations effectively sent the message that marginalized African Americans “[would] never stand silent” in the face of racism or discrimination.

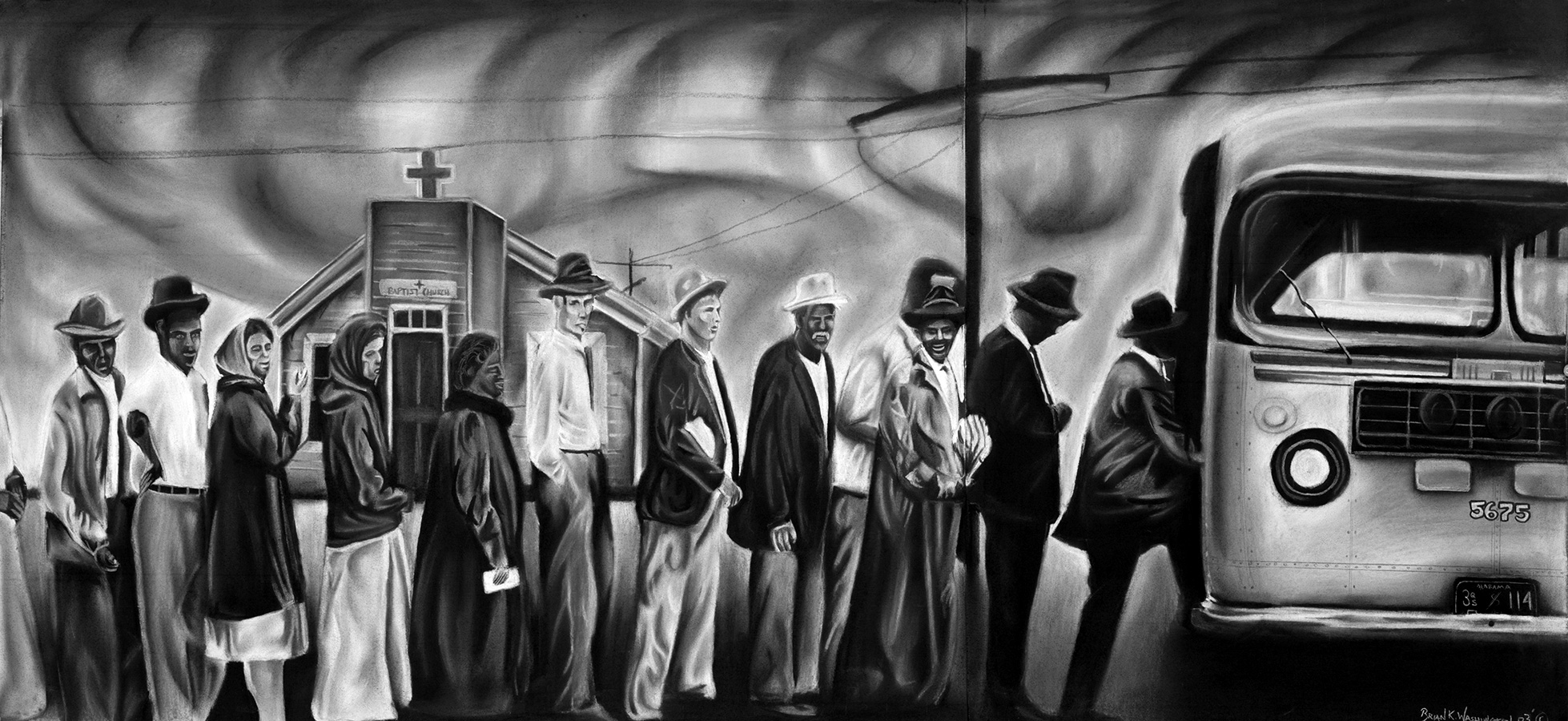

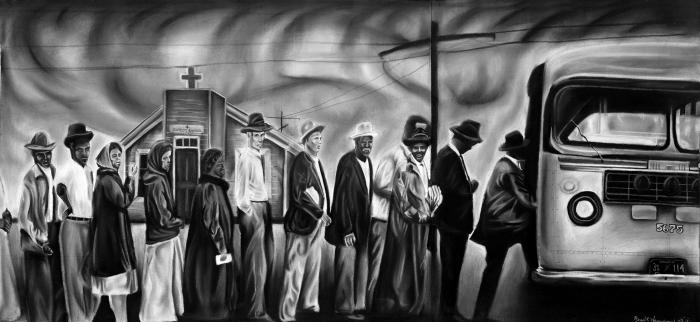

Get on the Bus

Another nonviolent tactic effectively employed by the activists of the Civil Rights Movement was the protest laden bus journeys referred to as “Freedom Rides.” These were journeys by Civil Rights activists on interstate buses into the segregated south to integrate seating patterns on buses and desegregate bus terminals.

Freedom Rides proved to be a dangerous mission, and in one instance a bus was firebombed, forcing its passengers to flee for their lives. Nevertheless, the freedom riders continued their rides into the segregated south, where they were often arrested for "breaching the peace" by using "white only" facilities.

Freedom riders paid a heavy price for racial justice. Often, when they stepped off buses in segregated terminals, angry mobs were waiting, armed with baseball bats, lead pipes, and bicycle chains.

Get On The Bus

In “Get On The Bus,” Washington depicts a group of Freedom Riders preparing for a ride through segregated Alabama. The activists board the bus in front of a Baptist church, which symbolizes the Freedom Movement’s foundation on the principles and of the southern African American Church. The steeple of the church is in the shape of a cross, and cuts against the ominous and turbulent skies, symbolizing the importance that religious faith played for these brave activists who risked their personal well-being for the sake of social change.

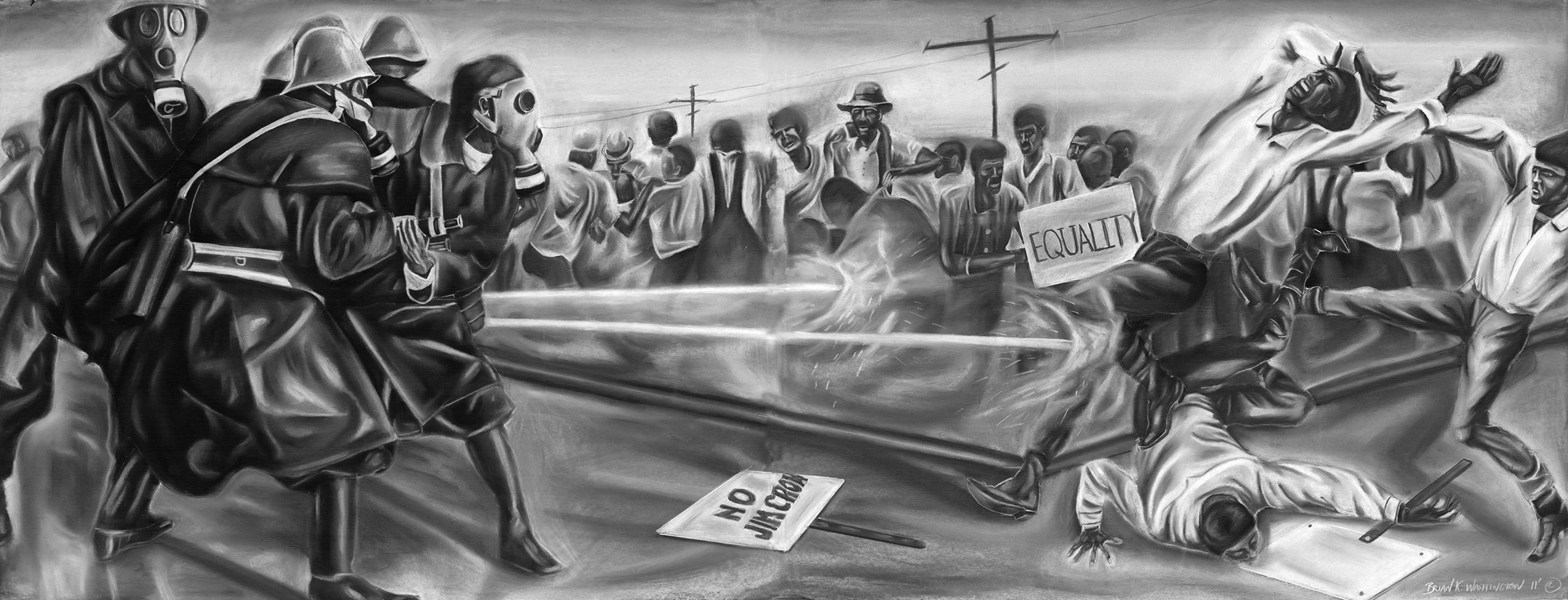

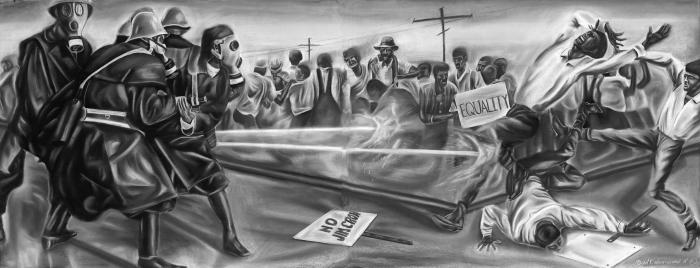

Freedom Has Never Been Free

At times, the Civil Rights Movement degenerated into brutality inflicted at the hands of segregationists, police officers and local authorities in southern communities. Police aimed high-powered hoses and unleashed snarling dogs on black men, women and even children who wanted just one thing — to be treated the same as white Americans.

Freedom Has Never Been Free

In “Freedom Has Never Been Free,” Washington depicts the brutality of the Civil Rights Movement at its climax. Fire hoses were used on protesters -- whether they were men or women, peaceful or not – as a means to disrupt their dreams of racial equality. When that was not enough, firefighters turned even more powerful hoses on protesters, hoses that shot streams of water strong enough to break bones and roll the protesters down the street. Sometimes protesters suffered from more than just fire hoses; they were sometimes beaten or even killed.

Washington implicates all of these details into the composition of “Freedom Has Never Been Free.” To the right, protesters stumble and fall as they are drenched with the violent waters shot at them by local firemen. The firemen, the villains of this work, are adorned with masks that obscure their faces, and substitute their humanity for a ghastly, otherworldly existence. The protesters in the center of the image have bound their arms together, in an attempt to withstand the pulverizing force of the fire hoses -- hoping that their collective strength can withstand the power of the firemen’s tools of oppression.

To the center right is a lone protester holding a sign that reads “EQUALITY,” reminding the viewer that this horrific scene was born out of the desire for African Americans to have the same rights as white Americans.

Some Truths Are Not Self Evident

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…”

The activists of the Civil Rights Movement set out to use nonviolent tactics to convince segregationists of this universal truth – that “all men are created equal.” Although these activists eventually prevailed in changing the country based upon their heroic efforts, for many segregationists in the south, the equality of all men was not a self-evident truth.

Some Truths Are Not Self Evident

In “Some Truths Are Not Self Evident,” Washington depicts the conflict-ridden nature of social change in the segregated south. During this era, thousands of civil rights protesters were arrested – and many were assaulted with high-pressure fire hoses, shocked with electric cattle prods, and beaten by police as well as angry segregationists. The protesters suffered these consequences simply for demanding equality for all human beings. Despite the violence, the activists persevered and many of the demonstrations escalated.

Washington employs three central images in “Some Truths Are Not Self Evident,” which are meant to be interpreted together as a singular whole. On both of the side panels, Washington depicts protesters suffering the consequences of their bravery. Both the men depicted on the left, and the woman depicted on the right, are seen falling victim to the brutality of local authorities who have reduced themselves to the use of abject violence. The image of a gazing eye fills the center of the painting, symbolizing the need for focus in times of tribulation -- the need for each member of the Freedom Movement to keep their “eyes on the prize” of achieving racial equality for all Americans.

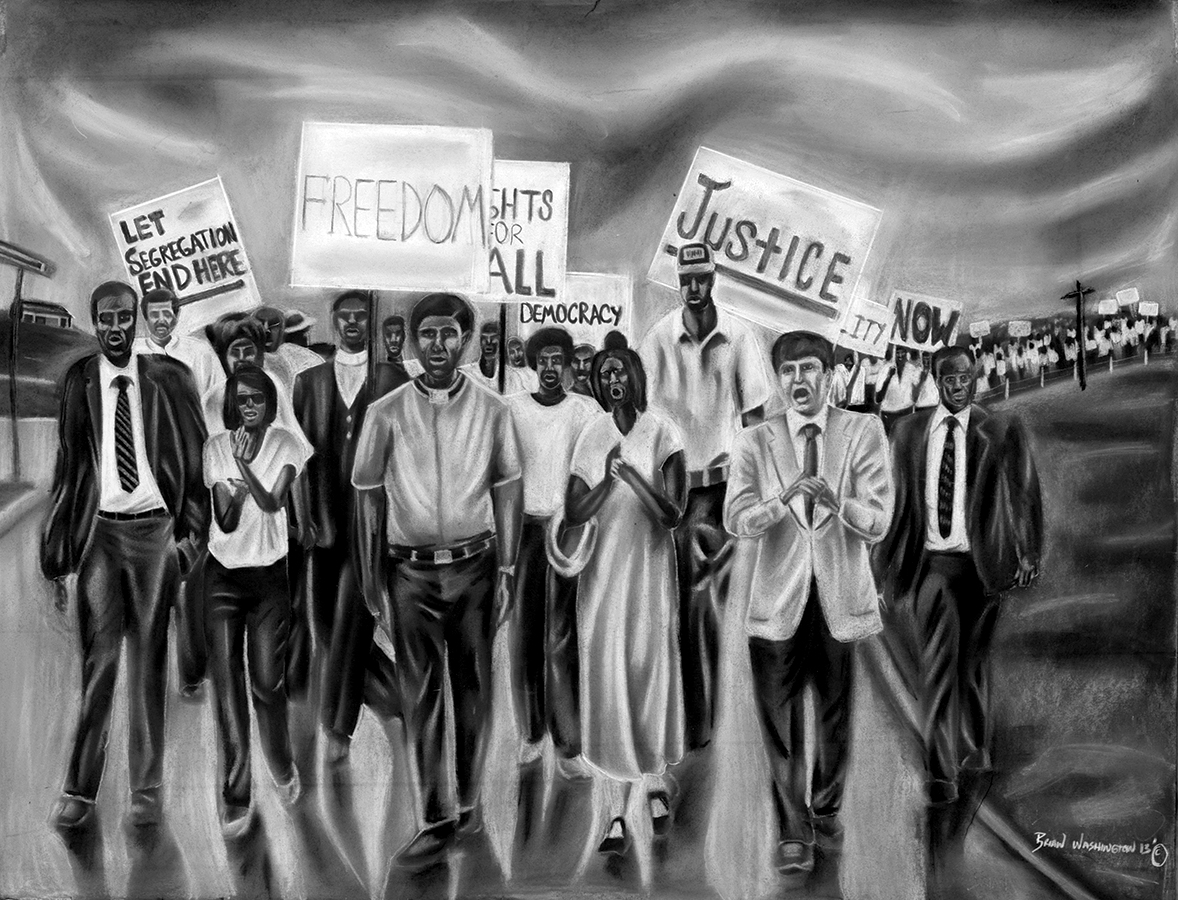

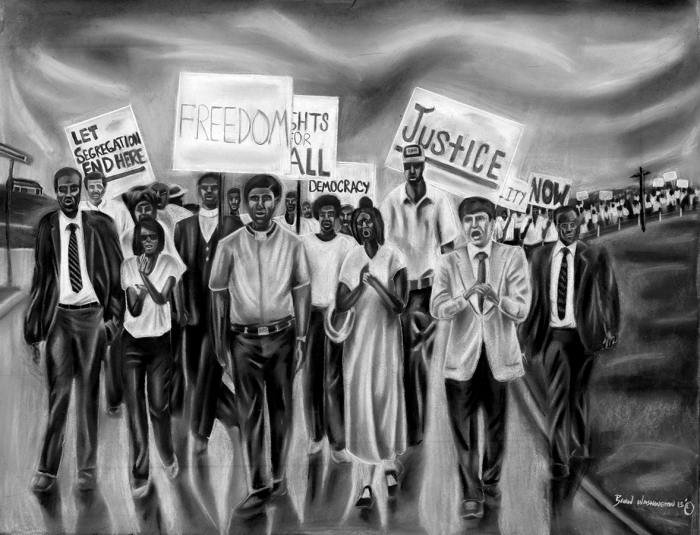

Let Nobody Turn Us Around

In response to non-violent protest, many business communities in the South -- fearing damage to their commercial interests -- eventually agreed to integrate lunch counters and hire more African Americans. These changes were often made over the objections of city officials, providing the Freedom Movement with a much-needed victory.

Let Nobody Turn Us Around

In “Let Nobody Turn Us Around,” Washington depicts a traditional Civil Rights era protest scene, featuring a crowd of demonstrators taking to the streets to fight segregation and Jim Crow. As a result of these protesters’ non-violent tactics (which were commonly met with brutal violence from southern authorities), many of the segregationist policies of the south were eventually overturned.

A Seeming Contradiction

The word “paradox” is defined as:

“[A] statement or proposition that seems self-contradictory or absurd but in reality expresses a possible truth.”

In many respects, the violent response by southern segregationists to nonviolent and peaceful protests for equal rights by African Americans was the ultimate paradox -- a “seeming contradiction” of logic and moral reasoning.

Ironically, however, such violent reactions to peaceful protests eventually started to win people over to the cause of Civil Rights. Police officers brazenly attacked protesters -- and the television cameras covering the drama broadcasted their brutality to the rest of the country. This inhumanity swayed many people who were indifferent to the cause to support it as the moral thing to do, and strengthened the conviction of those who already believed in Civil Rights.

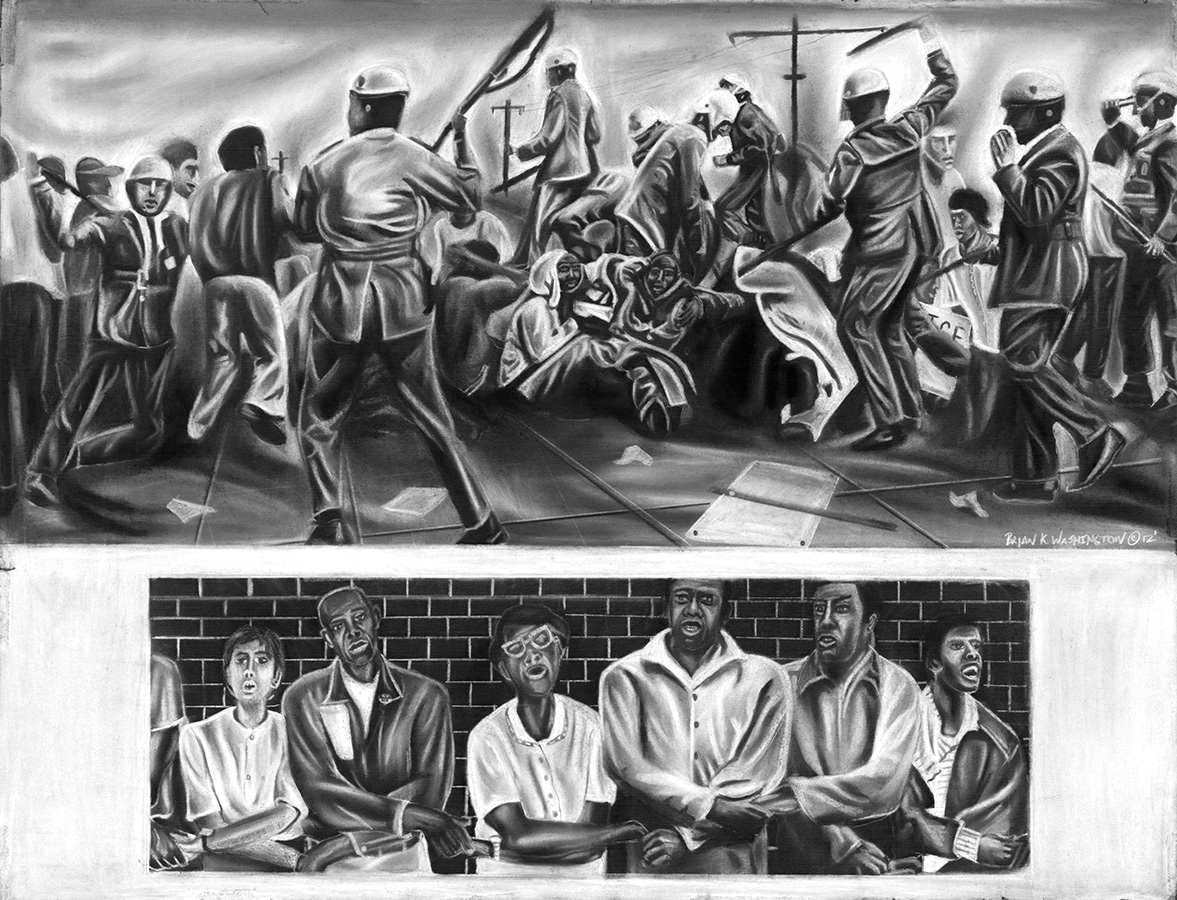

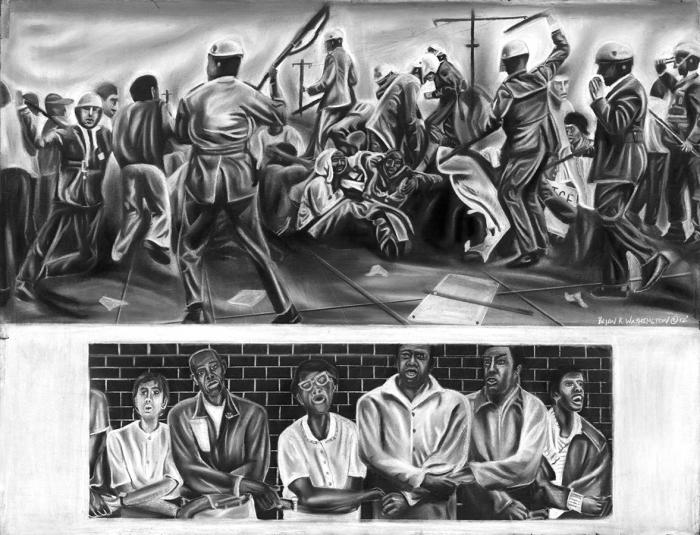

A Seeming Contradiction

In “A Seeming Contradiction,” Washington illustrates the paradoxical nature of the civil rights related violence that ravaged the American south. Washington juxtaposes the images of peaceful protestors singing freedom songs, with images of brute force used by southern authorities hoping to stifle attempts at social progress.

We Walk The Difficult Road

On "Bloody Sunday," March 7, 1965, some 600 civil rights marchers headed east out of Selma on U.S. Route 80. They got only as far as a local bridge six blocks away, where state and local lawmen attacked them with billy clubs and tear gas and drove them back into Selma. Two days later on March 9, Martin Luther King, Jr., led a "symbolic" march to the bridge. Then civil rights leaders sought court protection for a third, full-scale march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery.

Less than five months after the last of the three marches, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 -- the best possible redress of grievances at the time. This was an enormous victory for not only the Civil Rights Movement and its participants, but also a landmark in the overarching Freedom Movement for equality that began with exploited southern sharecroppers in the Reconstruction Era south.

We Walk The Difficult Road

“We Walk The Difficult Road” was inspired by the Selma-to-Montgomery March for voting rights. The Selma-to-Montgomery March for voting rights ended three weeks -- and three separate events -- that represented the political and emotional peak of the modern civil rights movement.

In “We Walk The Difficult Road,” Washington depicts a racially mixed group of activists, some carrying American flags, marching in support of voter rights in the rural south. Ominous and sweeping clouds foreshadow and completely obscure armed National Guardsmen standing road-side. Indeed, for legions of brave activists participating in the Selma-to-Montgomery March, the road to freedom was difficult – but the ultimate success in changing the racially divisive social landscape of the South was monumental.

What These Weathered Eyes Have Seen

By the height of the formally recognized Civil Rights Movement, many elder African Americans had lived through and experienced heart wrenching manifestations of discrimination and disenfranchisement, including sharecropping, segregation, lynchings, and police brutality. These years of pain were often visible in the worn facial expressions and features of African Americans who had lived through the struggle -- a continual struggle -- that had demonstrated significant signs of progress but was far from over.

What These Weathered Eyes Have Seen

In “What These Weathered Eyes Have Seen,” Washington depicts the troubled eyes of an otherwise unidentified elderly African American man. The man’s aged and weathered eyes possess a hint of sadness, yet speak to the trying experiences of a people and the need for persistence in times of adversity.

Part Three

The Civil Rights Struggle

The Civil Rights Movement: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

The enormous gains of the Freedom Movement stand to last a long time. However, the full effects of these gains are yet to be felt in American society. The struggle for equality is founded on the sacrifices and accomplishments of the brave activists of the Civil Rights Era, and those who supported them. By demonstrating the conflict ridden nature of social progress, these activists have bestowed modern Americans with a blueprint of the persistence, resolve, and fortitude required to create true social change.

"Equal rights" struggles now involve multiple races, as well as the issues of rights based upon gender and sexual orientation. Racism has lost its legal, political, and social standing, but the legacy of racism-- poverty, ignorance, and disease – still confronts American society in a very real way. For America to live up to its true creed, the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal” must be fully realized.

Until we meet that day, the struggle continues.

- Brian Washington